In the last 30 years, a field has emerged that is primed to dramatically influence the way we teach our classes, the way we shape our learning environments, perhaps even the way we think about education. Reading headlines today, we would all be forgiven for suspecting that that field is technology: since the early 80s, driven by a massive economic engine, technology has poured into schools and enabled imaginative learning environments and opportunities. And now, we are investing heavily as a nation into technology as the key to education’s ills.

Here, we can see the arrival of the personal computer and the growth of the internet. And if we superimpose the graphs of the technology terms with cognitive science, we see their presence in the public mind in relation to each other.

This is the first of fourteen posts in a series about the role cognitive science in education.

Cognitive Science, The Next Education Revolution, includes:

Introduction:

These posts are adapted from a talk presented at SXSWedu on March 6, 2013.

This is great. Our technological advancements have limitless potential, but at this moment in history we’re putting the cart before the horse. We’re putting the object of delivery ahead of the engine that should power it.

For what has also flourished in the last 30 years is the field of cognitive science.

Our understanding of the mechanics of the human mind has deepened enormously, and this understanding already has begun to affirm much of what we know about what works in education, while also revealing new ideas and strategies for how to improve what we do. This understanding is starting to validate our pedagogical philosophies and challenge our curricular organization. It’s starting to offer insight into the science of learning--to complement and inform what we know about the art of teaching.

But we have no great economic engine to drive this advancement, to push it into schools. We have invested relatively little into the sharing of the science of learning with our teachers. And we can see these two fields--cognitive science and technology--growing in the context of the other.

Google’s NGram Viewer and what we write about

Google’s NGram Viewer, which shows how often a word appears in the corpus of literature scanned into Google Books, reveals the remarkable rise of cognitive science in the public consciousness:

In the twentieth century, we see the rise of the behaviorist approach to psychology. Later, we see the growth of the cognitive approach to psychology, and then the broader field of cognitive science.

Moving into the first decade of the 21st century, we can see the ascent of neuroscience in the public consciousness, overtaking even its parent field of study, cognitive science. It’s the kid brother to cognitive psychology, and while it's young yet, it’s gotten a lot of attention recently, and we are only just beginning to glean its value. Nonetheless, through these four lines, we can see the arrival of modern psychology in the public’s mind.

Moving into the first decade of the 21st century, we can see the ascent of neuroscience in the public consciousness, overtaking even its parent field of study, cognitive science. It’s the kid brother to cognitive psychology, and while it's young yet, it’s gotten a lot of attention recently, and we are only just beginning to glean its value. Nonetheless, through these four lines, we can see the arrival of modern psychology in the public’s mind.

But what about technology?

Cognitive science is dwarfed by the internet. Add the word “technology,” and we see the amount of writing on technology relative to the amount of writing on the brain sciences:

It's not even close, and this seems an accurate reflection of the dominance of technology in our modern mindset. Technology is all the rage, and the sciences of the mind are but a distant echo in comparison.

Cognitive Science goes public

We are, nonetheless, seeing some convergence of cognitive science and education:

Cognitive Science goes public

We are, nonetheless, seeing some convergence of cognitive science and education:

Online education organizations are incorporating research into their design. Coursera, for instance, dabbles in the science, grounding their quiz practice around research on retrieval. Memrise, a startup built around memory training, goes further in its pedagogy, seeking to richly encode vocabulary terms. And Lumosity is doing some of the most interesting work at the intersection of the online space, cognitive abilities, and games.

Offline, we’re seeing other ways in which cognitive science is entering the learning space. Companies like CogMed are working with schools to directly train working memory and attention. The Learning and The Brain conference series brings brain scientists and educators together. And some universities have a Mind, Brain, and Education masters track at their Graduate Schools of Education.

And in the press, newspaper science sections are filling up with pictures of the brain lighting up with rainbow-colored splotches, some journals even focus solely on research-based news, and bloggers like Annie Murphy Paul are exploring the “science of smart.”

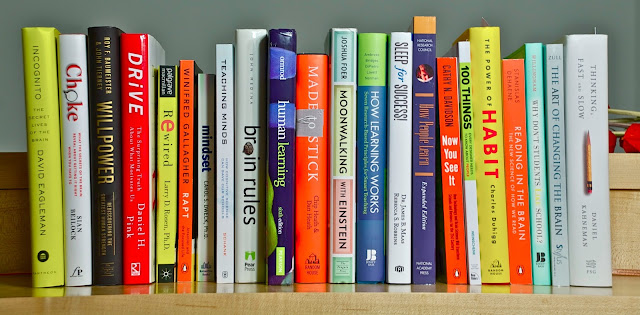

Concurrent with all this, we’ve seen a proliferation of books that have sought to popularize the growing body of brain research out there. “Blink,” “Drive,” “Choke,” and other books with one-word titles (on the left) promote “secret” and “surprising” truths discovered by researchers about motivation, willpower, and the like. Others collect research related to education or specific activities, like sleep, memory, reading, and more. These books offer welcome insight, and they're all fairly new; almost all of the books above were published in the last five years.

A Bias Towards Science

All this indicates that research into how the brain works has exploded. And as a result, increasingly, we seem to be living in scientific times, times in which we only seem to believe something if it’s backed up with a phrase like: “studies show” or “recent research indicates.” I teach English, and even in my department, a proposal about changing an approach to the curriculum summons questions asking for a study that proves that the proposal is a good one.

Interestingly, this scientific bias wasn’t always the case. Once, our philosophers and artists were the authorities, and even in the dawn of the scientific era, people we now think of as scientists and mathematicians--like Galileo, Descartes, and Newton--were called “philosophers.” But the age of “I think therefore I am” seems to have changed to “Recent research indicates I am thinking... therefore I am.”

Here’s the key point:

I believe we’re hitting a critical mass of knowledge in this field. Modern cognitive science has arrived; it's beginning to enter the public consciousness, and we have so much information, so much knowledge, so many studies, so many books. But in this age of information overload, it is hard to know how to prioritize it, how to make sense of it all. As a teacher, I have 1000 studies that tell me what works with the human mind: how mindsets influence learning, the importance of socio-emotional safety, and much, much more--but I can’t keep track of the 1000 instructions and still keep in mind my daily, weekly, and longer objectives.

And so the time is ripe for educators to synthesize and organize what we know about cognitive science and the inner workings of the brain in a way that offers consistently useful, practical guidance. What we need is something we can apply on a year-long planning scale and on a daily planning scale. Something that can help us both to create richer, more effective learning experiences, and to help us analyze and understand our students’ cognitive experiences in real time.

The blog posts that follow this one are an effort to provide this synthesis. It’s a work in progress, and it comes not only from reading research, studies, and textbooks, but also from reading works by artists, designers, and philosophers--for they often see the future most clearly, and science, it seems, is often catching up to the vision and intuitive understanding that artists have had for centuries.

I write about this first and foremost to provide practical access and insight for teachers into the cognitive science of learning. It’s the synthesis that I've wanted since I first encountered the brain sciences as a graduate student. It's what I use for myself when I think about crafting and analyzing the learning experience I provide for my students.

But I also share this in hopes that it might propel the collective attention of the ed tech space further towards cognitive science so that agents in the exploding educational technology market can more fully and deliberately design their work in ways that make constructive, deep learning environments for students--not just flashy apps with gimmicks, gizmos, and gadgets that seem cool.

I like cool. I really want an iPad mini. But I like learning better.

This is the first of fourteen posts in a series about the role cognitive science in education.

Cognitive Science, The Next Education Revolution, includes:

Introduction:

- Cognitive Science: The Next Education Revolution (Part 1 of 14)

- A Cognitive Model for Educators: Attention, Encoding, Storage, Retrieval (Part 2 of 14)

- Attention: the "Holy Grail" of Learning (Part 3 of 14)

- Encoding: How to Make Memories Stick (Part 4 of 14)

- (Interlude) Long Term Memory and Working Memory (Part 5 of 14)

- Storage I: How Memory Works - Redux (Part 6 of 14)

- Storage II: Sleep and Memory (Part 7 of 14)

- Retrieval: Getting and Forgetting (Part 8 of 14)

- Cognitive Design: Essential Questions for Educators (Part 9 of 14)

- Character and Success... and the Cognitive Model (Part 10 of 14)

- Towards a Unification of Pedagogies (Part 11 of 14)

- Why Old School and New School Aren't in Conflict (Part 12 of 14)

- Technology, The Brain, and Teaching (Part 13 of 14)

These posts are adapted from a talk presented at SXSWedu on March 6, 2013.

Comments

Post a Comment