Encoding is what happens when information meets the brain.

Let's look a little closer...

Multi-Sensory Experience

Information with anchors--richly encoded one way or another--that is what we learn and remember.

This is the fourth of fourteen posts in a series about the role of cognitive science in education.

To have future posts delivered to your inbox, choose "subscribe" from the bar on the right side of the screen.

During exposure to new information, the brain does two things: first, it processes sensory and emotional information, and then second, it tries to attach this new information to old information, to prior knowledge. And the richer the sensori-emotional experience and the deeper the well of prior knowledge, the more strongly the new information is encoded into memory.

And so, strong learning grows out of two things: full, multi-sensory experiences and/or richly contextualized information.

Multi-Sensory Experience

Several years ago, the science department where I teach switched to a Physics First curriculum. Like most schools, we had previously taught biology in the freshman year. But, one teacher told me, at a department meeting one day, the science teachers asked themselves: “What is it that led us to become science teachers? What turned us on to science to begin with?”

And their answer to that question was that they remembered observing physical phenomena, getting their hands on things and playing with them. This physical experience with objects, their experience asking questions and experimenting with visible, tangible stuff, was what first developed their scientific thinking. It was what hooked them on science.

And so as a result, the science department inverted the 9th and 11th grade years. They now teach physics first and a more advanced biology class to juniors. Now, the freshman year is largely spent handling and experimenting with directly observable physical materials. Students develop primary sensory experience with physical and scientific principles.

And subsequent to this move, we’ve seen a jump in students taking advanced science courses in later years.

This seems the fulfillment of philosophies that have been around for ages:

Dewey and Aristotle both promote experiencing information in the most direct, authentic, multi-sensory way. And we can unpack Dewey’s phrase “impress the mind” to understand that the more we see, touch, feel, and experience what we seek to learn, the better we learn it, the more we impress it into our memory.

Dewey and Aristotle both promote experiencing information in the most direct, authentic, multi-sensory way. And we can unpack Dewey’s phrase “impress the mind” to understand that the more we see, touch, feel, and experience what we seek to learn, the better we learn it, the more we impress it into our memory.

We’ve known about this for some time, and this is what immersive, experiential education is all about. It’s why we create, easily recall, and enjoy multi-sensory experiences.

And so, the richer the sensory-emotional experience of new information is, the more deeply it is encoded into the brain.

Prior Knowledge

And the added benefit of these kinds of primary experiences is that they fuel our learning later on.

When we have vivid and strong prior knowledge about a subject, we have access and insight into new related, knowledge. When we have previous experience with something, we can encode new information more effectively and more richly.

The sentence above makes little sense on a first read. Notes and seams? What’s going on here? But, when supplied with a little bit of prior knowledge (for example, that the sentence describes a damaged bagpipe), we are suddenly able put the sentence into a context. We can associate the words with prior knowledge we have. We have a hanger upon which to drape new information.

And this is the second form of encoding: attaching new information to old information, to prior knowledge.

In a recent conversation, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer John McPhee spoke about the relationship between our previous experiences--our prior knowledge--and our present interests. He said it like this:

He describes here how attention works like a filter, and he proposes that we attend to what we already know, that we attend to what we have previous interest in and experience with.

And if the first key takeaway about encoding is that multi-sensory experiences are encoded more richly into the brain, then the second key takeaway about encoding is that we attach new experiences to prior experiences, to prior knowledge. And the more prior knowledge we have, the more hangers we have to drape our new knowledge on, the more richly we can encode and associate new information.

McPhee here is onto the close relationship between attention and encoding, that what we attend to feeds what we know, and what we know feeds what we attend to.

Summary

Educators often talk about teaching to multiple sensory pathways, and it is absolutely accurate to say that providing a variety of sensory and emotional experiences with content enables students to learn better. Indeed, students encode information in more ways when they see, touch, move, and hear information.

But equally as important is how richly that information is contextualized. When students have prior experience with a subject, they have a context within which they can understand the new information. The value of this cannot be overstated.

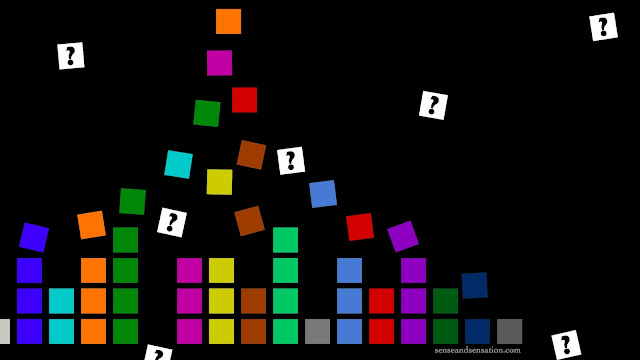

Information without anchors--information that is abstract and incomprehensible, or information that has no connection to what we already know--it passes through us, like the little white boxes with question marks above, sinking off the page and out of sight.

Information with anchors--richly encoded one way or another--that is what we learn and remember.

But what happens after information is encoded into the brain? What is the half-life of knowledge? What makes memory last? These questions we’ll explore in coming posts.

This is the fourth of fourteen posts in a series about the role of cognitive science in education.

Introduction:

- Cognitive Science: The Next Education Revolution (Part 1 of 14)

- A Cognitive Model for Educators: Attention, Encoding, Storage, Retrieval (Part 2 of 14)

- Attention: the "Holy Grail" of Learning (Part 3 of 14)

- Encoding: How to Make Memories Stick (Part 4 of 14)

- (Interlude) Long Term Memory and Working Memory (Part 5 of 14)

- Storage I: How Memory Works - Redux (Part 6 of 14)

- Storage II: Sleep and Memory (Part 7 of 14)

- Retrieval: Getting and Forgetting (Part 8 of 14)

- Cognitive Design: Essential Questions for Educators (Part 9 of 14)

- Character and Success... and the Cognitive Model (Part 10 of 14)

- Towards a Unification of Pedagogies (Part 11 of 14)

- Why Old School and New School Aren't in Conflict (Part 12 of 14)

- Technology, The Brain, and Teaching (Part 13 of 14)

Comments

Post a Comment